In the Key of Nira Ghani

In the Key of Nira Ghani Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water Lark and the Dessert Disaster

Lark and the Dessert Disaster Terminate

Terminate Sneaker, Sandals, & Stilettoes: Fairy Tales for the Well-Heeled Princess

Sneaker, Sandals, & Stilettoes: Fairy Tales for the Well-Heeled Princess Burned

Burned Feuding Hearts

Feuding Hearts Lark Takes a Bow

Lark Takes a Bow Lark Holds the Key

Lark Holds the Key Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand The Cowgirl & the Stallion

The Cowgirl & the Stallion Gatekeeper

Gatekeeper Lark and the Diamond Caper

Lark and the Diamond Caper Across the Floor

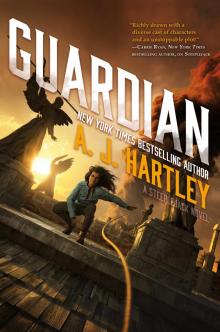

Across the Floor Guardian

Guardian Game's End

Game's End